- October 15: A picture is worth a thousand words

Lesson One: Introducing students to the art of speaking and listening

Lesson One: Introducing students to the art of speaking and listeningOn Thursday I began my Field Study about using scaffolding activities for storytelling. The children in my class are young and I already knew that I would have to introduce each step slowly and carefully. I decided to use the game “Virginia Reel” to practice listening and speaking. To a partner, the students would share 3 things: their name, age and something that they liked to do. Before the game, we practiced speaking these sentences “in our heads” first. This gave the students an opportunity to quietly think through the process. A few students came to the front of the class and shared their stories for all of us as examples. Then, in 2 lines, face to face, the students told their stories to a partner. Some were loud and animated. Others shy and reserved. There were active – and not so active – listeners. I quickly grabbed my camera and got a shot of these interactions.

Instead of reviewing the behaviours of being an active listener and a clear speaker on a t-chart like I have done in the past, I put the picture under the doc. camera and we debriefed it as a class. I saw a number of things happen. First, my role became that of a facilitator not the imparter of knowledge. I let the picture speak and teach. Students noticed, shared and made connections. They pointed out good and bad behaviours. They listened to each other. Secondly, in making observations, my students encouraged and affirmed each other. We saw some active listening and some great storytelling. One shy student in particular, used emotion and gesture when speaking. I saw students being built up by their classmates – naturally and honestly. Thirdly, the next day, when reviewing the Virginia Reel picture, my students remembered details and gave examples of the picture with little difficulty. The fact that most of them were in the picture gave importance to the event and allowed them to make personal connections. They could easily recall good and bad storytelling behaviours.

Scaffolding used: providing students with a framework for speaking, quiet thinking, student modelling, teaching (learning to stand in a line, facing a partner) and playing the game “Virginia Reel”, debriefing by discussing and sharing behaviours seen on the picture.

- October 16: Our Trip to the Pumpkin Patch

Lesson Two: Retelling and recording an experience using Adobe Voice

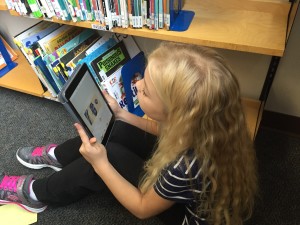

Lesson Two: Retelling and recording an experience using Adobe VoiceThis morning we went to the pumpkin patch. What a great experience to talk about! In the afternoon, we had some storytelling to do. First, we recalled the Virginia Reel game that we had played the day before. We used the same speaking format except this time the students were to tell one or two things that they had enjoyed at the farm. Second, we had to learn how to use the Adobe Voice App on the i-pads in order to record our sharing. This was a bit more difficult, as many of the students were more interested in the i-pad than the actual App. I was fortunate to have the guidance of our District Technology Helping Teacher as I wasn’t familiar with Adobe Voice either. Anticipating this, we set up the i-pads in advance. Still, there were a number of steps to follow and I was thankful for the two other adults in the room to help with trouble shooting.

For many of my students, this activity was a lot of fun. They quickly understood how to use Adobe Voice and moved beyond today’s expectations. They enjoyed listening to themselves and being able to re-record if they wanted to make changes. Jack did a little experimenting with expression and Tanner extended the activity by talking about 2 pictures instead of just one. I was interested however, that this activity was visibly stressful for two students. One student, Jordan, quickly put up his hand and said that he didn’t want to speak into the mic. Jordan is generally quiet and doesn’t feel comfortable sharing ideas in large group situations. He was OK with the suggestion to move away from his peers but still acted silly in recalling his experiences. Teiya started crying, and said it was too loud in the class to hear herself record. She was fine after finding a quiet spot to share her story.

For many of my students, this activity was a lot of fun. They quickly understood how to use Adobe Voice and moved beyond today’s expectations. They enjoyed listening to themselves and being able to re-record if they wanted to make changes. Jack did a little experimenting with expression and Tanner extended the activity by talking about 2 pictures instead of just one. I was interested however, that this activity was visibly stressful for two students. One student, Jordan, quickly put up his hand and said that he didn’t want to speak into the mic. Jordan is generally quiet and doesn’t feel comfortable sharing ideas in large group situations. He was OK with the suggestion to move away from his peers but still acted silly in recalling his experiences. Teiya started crying, and said it was too loud in the class to hear herself record. She was fine after finding a quiet spot to share her story.Upon refection, today’s storytelling activity had many learning opportunities – and perhaps potential difficulties. Orally retelling stands alone as a skill that one needs to become comfortable doing. It also requires much practice. Learning to use Adobe Voice is a skill that includes using the App as well as feeling comfortable enough to record and listen to oneself speak. Combining these two together on a Friday after was a challenge for me as the teacher as well as for my students. Both of us being learners! I am excited to try this again in the future. I am now more aware of the need that some of my students have for privacy and quiet – especially as beginners. I am aware that some of my students express their uncomfortable feelings by being silly on the recordings. I need to address this. I will create more opportunities for students to expand their storytelling abilities. I will not always use Adobe Voice. Students should learn to speak in other forums as well.

Scaffolding in this lesson: going to the pumpkin patch (having a real life story to tell), reviewing and practicing using the same format as yesterday (3 ideas), practicing telling the pumpkin patch story to a buddy and modelling it in front of the class, learning the steps to use Adobe Voice (some of these steps were already step up in the App), trying out and experimenting with telling and recording the story on the i-pad.

- October 25: Vygotsky and Scaffolding

Today I spent much of the afternoon reading about Vygotsky and the Zone of Proximal Development. I have heard about ZPD many times, but not through the lense of Vygotsky’s theory. I was overwhelmed by the vocabulary and knowledge; having to read the same paragraph over and over again to grasp some kind of understanding. I was curious as to how I had been interpreting this idea in my own classroom. Was I unknowingly seeking out and giving instruction/support at “just the right time”? The idea of supporting students at this optimal ZPD made me think of scaffolding in particular. Perhaps also, because I was intending to scaffold student learning when teaching storytelling for my Field Study. At this point, I believe that I am using the term “scaffolding” quite loosely when approaching the lesson planning. I am interested in developing a more articulated view of scaffolding and how it connects with Vygotsky’s theory of ZPD. I am curious if/how the two ideas overlap and whether the answer will bring clarity to my teaching of storytelling to my students.

Today I spent much of the afternoon reading about Vygotsky and the Zone of Proximal Development. I have heard about ZPD many times, but not through the lense of Vygotsky’s theory. I was overwhelmed by the vocabulary and knowledge; having to read the same paragraph over and over again to grasp some kind of understanding. I was curious as to how I had been interpreting this idea in my own classroom. Was I unknowingly seeking out and giving instruction/support at “just the right time”? The idea of supporting students at this optimal ZPD made me think of scaffolding in particular. Perhaps also, because I was intending to scaffold student learning when teaching storytelling for my Field Study. At this point, I believe that I am using the term “scaffolding” quite loosely when approaching the lesson planning. I am interested in developing a more articulated view of scaffolding and how it connects with Vygotsky’s theory of ZPD. I am curious if/how the two ideas overlap and whether the answer will bring clarity to my teaching of storytelling to my students.Reference: Chaikin,S. The Zone of Proximal Development in Vygotsky’s Analysis of Learning and Instruction. In A.Kozulin, B.Gindis, V.S.Ageyev, S.M.Miller (Eds.), Vygotsky’s Educational Theory in Cultural Context. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- October 28: Being the Storyteller

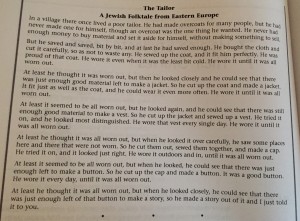

Lesson Three: I love to tell stories to my class. I find that when I tell stories, I can really connect with my students. I feel an emotional bond because I am able to physically move around them, make eye contact, feel their own emotion and reaction to me – and then react back to them with what I perceive they need to make the story come alive. It’s a constant back and forth communication where they give to me and I give back to them. In the past I’ve told personal stories – of my dog or cat, family member or activity that I’ve been involved in. Today, however, I told them a story that I had read and memorized called “The Tailor”.

I was a bit apprehensive about remembering the details but I purposely chose a story that had repetition both in the text and in the story line. That was good for me and also for my students. I could tell they were already predicting the sequence and enjoyed saying the repetitive parts along with me. This interaction – between storyteller and listeners – was most enjoyable! Hamilton and Weiss in their book, “Children Tell Stories” suggest that “if you wish to convince your students to tell stories, you must tell a story yourself! By telling stories you provide an effective model for risk taking and good-quality oral language for students. You demonstrate the tools that students need to share the pictures, stories and feelings in their own creative minds, both orally and in writing. Perhaps, most important of all, you inspire them.” (2005, 27).

Lesson Three: I love to tell stories to my class. I find that when I tell stories, I can really connect with my students. I feel an emotional bond because I am able to physically move around them, make eye contact, feel their own emotion and reaction to me – and then react back to them with what I perceive they need to make the story come alive. It’s a constant back and forth communication where they give to me and I give back to them. In the past I’ve told personal stories – of my dog or cat, family member or activity that I’ve been involved in. Today, however, I told them a story that I had read and memorized called “The Tailor”.

I was a bit apprehensive about remembering the details but I purposely chose a story that had repetition both in the text and in the story line. That was good for me and also for my students. I could tell they were already predicting the sequence and enjoyed saying the repetitive parts along with me. This interaction – between storyteller and listeners – was most enjoyable! Hamilton and Weiss in their book, “Children Tell Stories” suggest that “if you wish to convince your students to tell stories, you must tell a story yourself! By telling stories you provide an effective model for risk taking and good-quality oral language for students. You demonstrate the tools that students need to share the pictures, stories and feelings in their own creative minds, both orally and in writing. Perhaps, most important of all, you inspire them.” (2005, 27). - October 29: Learning to Make a Story Map

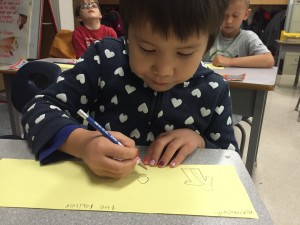

Lesson Four: One of the first ways to scaffold story telling in my class was to teach the students how to make a story map. A story map is a series of pictures that helps the teller to remember the sequence of events in the story. After telling the story “The Tailor” to my students, I had them draw the five different pieces of clothing that the tailor sewed. Each piece of clothing represented one part of the story line. We used a strip of paper and made sure that pictures they drew were simple – with little detail and no words. During the story telling I had introduced each section of the story with a picture that I had drawn.

From previous lessons, I knew that my young artists needed some drawing direction. So, to further scaffold this process, I provided the students with pictures that they could copy. I noticed that as the students worked, they spoke about the story, repeated the patterns and talked about the order. Drawing these pictures was helping them to internalize the story and begin the retelling process.

Scaffolding used: story mapping, providing picture examples for the students to copy

Lesson Four: One of the first ways to scaffold story telling in my class was to teach the students how to make a story map. A story map is a series of pictures that helps the teller to remember the sequence of events in the story. After telling the story “The Tailor” to my students, I had them draw the five different pieces of clothing that the tailor sewed. Each piece of clothing represented one part of the story line. We used a strip of paper and made sure that pictures they drew were simple – with little detail and no words. During the story telling I had introduced each section of the story with a picture that I had drawn.

From previous lessons, I knew that my young artists needed some drawing direction. So, to further scaffold this process, I provided the students with pictures that they could copy. I noticed that as the students worked, they spoke about the story, repeated the patterns and talked about the order. Drawing these pictures was helping them to internalize the story and begin the retelling process.

Scaffolding used: story mapping, providing picture examples for the students to copy - October 29: Telling the Wall

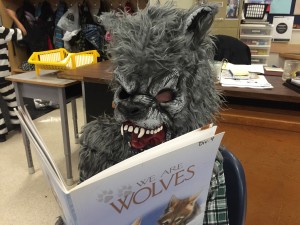

Lesson Five: The students were enthusiastic about the story “The Tailor” and the story maps that they had created.

I decided that it was time to give them the opportunity to re-tell the story. Before that however, we used a strategy called “telling the wall” to practice individual storytelling. With much direction and a bit of humour, we positioned ourselves facing the wall. To begin with, the student’s task was to say three things about themselves in a quiet, loud and scary voice. Some students found this to be awkward and needed some encouragement to stay focussed. Others enjoyed the challenge of hearing themselves speak – many said that their voices bounced back at them when they spoke. One student said that it was most fun to use his scary voice to speak:

“Telling the wall” was a creative and non-threatening way to practicing speaking. The wall acted like a neutral listener and surprisingly projected the students voices back to them. This strategy will definitely needed revisiting until the students feel comfortable standing and talking to the wall.

Scaffolding used: “telling the wall” strategy

Lesson Five: The students were enthusiastic about the story “The Tailor” and the story maps that they had created.

I decided that it was time to give them the opportunity to re-tell the story. Before that however, we used a strategy called “telling the wall” to practice individual storytelling. With much direction and a bit of humour, we positioned ourselves facing the wall. To begin with, the student’s task was to say three things about themselves in a quiet, loud and scary voice. Some students found this to be awkward and needed some encouragement to stay focussed. Others enjoyed the challenge of hearing themselves speak – many said that their voices bounced back at them when they spoke. One student said that it was most fun to use his scary voice to speak:

“Telling the wall” was a creative and non-threatening way to practicing speaking. The wall acted like a neutral listener and surprisingly projected the students voices back to them. This strategy will definitely needed revisiting until the students feel comfortable standing and talking to the wall.

Scaffolding used: “telling the wall” strategy - October 30: Telling the Wall Using a Story Map

Lesson six: Today’s lesson was about putting together a few of the scaffolding techniques we had learned. The students were ready to re-tell the story of “The Tailor” using their story maps as prompts and the wall as a listener. I reviewed the story, remembering to recall some of the repeated text (“at least it seemed to be all worn out”) and story patterns (the repeated use of articles of clothing). The students were then asked to find a place facing the wall and tell the story. A few things that I noticed: almost all of the children were engaged in the activity; the students used their story mapping prompts exclusively; a few students found it hard to get started and needed some support from me. Gavin, an ELL student spoke in short phrases without using any connections or repeated phrases.

Others, like Tanner and Marley were comfortable with the rhythm of the story and recalled the patterns and repeated portions easily. Veronique used a clear voice with some expression. Jordan, who often needs encouragement in speaking activities gave this task effort.

Scaffolding used: “telling the wall”, story mapping, storytelling

Lesson six: Today’s lesson was about putting together a few of the scaffolding techniques we had learned. The students were ready to re-tell the story of “The Tailor” using their story maps as prompts and the wall as a listener. I reviewed the story, remembering to recall some of the repeated text (“at least it seemed to be all worn out”) and story patterns (the repeated use of articles of clothing). The students were then asked to find a place facing the wall and tell the story. A few things that I noticed: almost all of the children were engaged in the activity; the students used their story mapping prompts exclusively; a few students found it hard to get started and needed some support from me. Gavin, an ELL student spoke in short phrases without using any connections or repeated phrases.

Others, like Tanner and Marley were comfortable with the rhythm of the story and recalled the patterns and repeated portions easily. Veronique used a clear voice with some expression. Jordan, who often needs encouragement in speaking activities gave this task effort.

Scaffolding used: “telling the wall”, story mapping, storytelling - Nov. 1: Climbing Up the Scaffolding Ladder

In order to move along in our storytelling process, I had to assess where we were at this point. I had given my students a number of opportunities to practice speaking on their own and then to others. In the beginning, the students had spoken about personal experiences (our trip to the pumpkin patch) and then we shifted to retelling the story “The Tailor”. I had infused student practicing with scaffolding activities such as the Virginia Reel, Telling the Wall, Round the Circle Storytelling and Telling to a Partner. We also worked on creating a story map and practiced introductions/endings. These things gave structure and acted as prompts for the tellers. Finally, I purposefully choose the story “The Tailor” because it contained patterns and repetitive parts. I felt these were important scaffolds for first time retelling.

In order to move along in our storytelling process, I had to assess where we were at this point. I had given my students a number of opportunities to practice speaking on their own and then to others. In the beginning, the students had spoken about personal experiences (our trip to the pumpkin patch) and then we shifted to retelling the story “The Tailor”. I had infused student practicing with scaffolding activities such as the Virginia Reel, Telling the Wall, Round the Circle Storytelling and Telling to a Partner. We also worked on creating a story map and practiced introductions/endings. These things gave structure and acted as prompts for the tellers. Finally, I purposefully choose the story “The Tailor” because it contained patterns and repetitive parts. I felt these were important scaffolds for first time retelling. - Nov. 2: The Power of a Picture

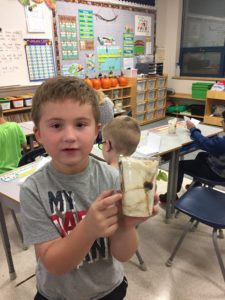

I spent some time looking through the pictures I had taken of my class last week. They varied. Some were intentional. I had taken them for data collection. They would serve as a purpose for my Field Study or student assessment. These spoke much about what we had been doing that day and addressed the learning objectives that I had tried to accomplish. They spoke to the intensity of my job: the demands of educational practice, keeping students motivated and teaching to individual needs and personalities. To be honest, many of them brought to mind a very busy, emotionally draining day. As I continued to scroll through the photographs I found myself smiling.

A warmth spread through me – the kind that teachers experience when they have made a connection with a student. Or when the humour of a situation allows itself to override all the complexities of the day. It is a good thing. A very good thing. It heals me of a cynical, critical heart and moves me to laughter and joy.

I am then thankful for the moments of memory a picture provides: a time for reflection and for seeing the good in my students, in my job and in me as a person.

I spent some time looking through the pictures I had taken of my class last week. They varied. Some were intentional. I had taken them for data collection. They would serve as a purpose for my Field Study or student assessment. These spoke much about what we had been doing that day and addressed the learning objectives that I had tried to accomplish. They spoke to the intensity of my job: the demands of educational practice, keeping students motivated and teaching to individual needs and personalities. To be honest, many of them brought to mind a very busy, emotionally draining day. As I continued to scroll through the photographs I found myself smiling.

A warmth spread through me – the kind that teachers experience when they have made a connection with a student. Or when the humour of a situation allows itself to override all the complexities of the day. It is a good thing. A very good thing. It heals me of a cynical, critical heart and moves me to laughter and joy.

I am then thankful for the moments of memory a picture provides: a time for reflection and for seeing the good in my students, in my job and in me as a person. - Nov. 5: Getting Ready

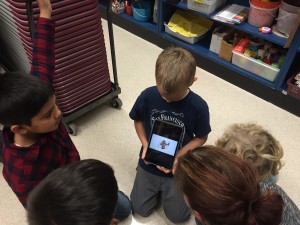

I learned a few things from the last time we used the Adobe Voice App on our i-pads. So before using it again, I made some changes. First, instead of using our school set of i-pads, I was fortunate to be able to borrow a set of five mini i-pads for long-term use. I could take these home and format them for each individual student. To prepare, I took pictures from the student’s story maps (with the Adobe Voice camera) and created 8 frames (an intro., 6 pictures and an ending) for each student. These frames would act as prompts for my students when they told their stories. I must admit, that this was time consuming. I realized though, that I was scaffolding their use of technology and with further practice, my students would be able to take pictures and prepare their own frames. Secondly, I decided that it would be more effective if my students could record privately in a quiet spot. It was a bit difficult to find places – a few of my students recorded in the art supply room! I was able to get another adult to circulate a few times and make sure my students were on task. With these changes in place I hoped for better results.

I learned a few things from the last time we used the Adobe Voice App on our i-pads. So before using it again, I made some changes. First, instead of using our school set of i-pads, I was fortunate to be able to borrow a set of five mini i-pads for long-term use. I could take these home and format them for each individual student. To prepare, I took pictures from the student’s story maps (with the Adobe Voice camera) and created 8 frames (an intro., 6 pictures and an ending) for each student. These frames would act as prompts for my students when they told their stories. I must admit, that this was time consuming. I realized though, that I was scaffolding their use of technology and with further practice, my students would be able to take pictures and prepare their own frames. Secondly, I decided that it would be more effective if my students could record privately in a quiet spot. It was a bit difficult to find places – a few of my students recorded in the art supply room! I was able to get another adult to circulate a few times and make sure my students were on task. With these changes in place I hoped for better results. - Nov. 6: Ready, Set, Record

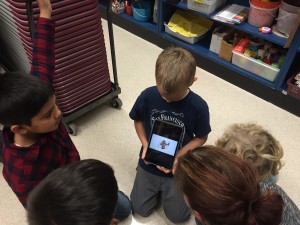

Yesterday we recorded our retellings of “The Tailor”. After so many opportunities to practice, the students were enthusiastic and ready to start. I had organized the i-pads and found places for the recordings to happen. Some initial observations in comparison to our first try (pumpkin patch recording) were:

1. Having students record in a quiet spot, away from distraction was much more effective. It was private, the students could concentrate, there were no opportunities to “show off” and surprisingly, they didn’t need much adult help. One student, Jack, did a wonderful job of retelling without acting silly like he had previously done. Personally, this method was less stressful for me as a teacher and definitely built my confidence as a user of technology.

2. Because this was our second time using Adobe Voice, the students were much more comfortable with the process. They weren’t distracted by the actual device and were able to move on to the actual recording.

3. I believe that the students were motivated by the “look” of their final product. The musical background, their own illustrations and the overall appearance of the recording was a good way to end this retelling. Many students asked if they could do it again.

4. To celebrate, we shared our storytelling recordings with each other. Although the students all told the same story, it was interesting to see how they personalized the retelling and made the story their own.

Yesterday we recorded our retellings of “The Tailor”. After so many opportunities to practice, the students were enthusiastic and ready to start. I had organized the i-pads and found places for the recordings to happen. Some initial observations in comparison to our first try (pumpkin patch recording) were:

1. Having students record in a quiet spot, away from distraction was much more effective. It was private, the students could concentrate, there were no opportunities to “show off” and surprisingly, they didn’t need much adult help. One student, Jack, did a wonderful job of retelling without acting silly like he had previously done. Personally, this method was less stressful for me as a teacher and definitely built my confidence as a user of technology.

2. Because this was our second time using Adobe Voice, the students were much more comfortable with the process. They weren’t distracted by the actual device and were able to move on to the actual recording.

3. I believe that the students were motivated by the “look” of their final product. The musical background, their own illustrations and the overall appearance of the recording was a good way to end this retelling. Many students asked if they could do it again.

4. To celebrate, we shared our storytelling recordings with each other. Although the students all told the same story, it was interesting to see how they personalized the retelling and made the story their own. - Nov. 6: Ready, set, recordYesterday we recorded our retellings of “The Tailor”. After so many opportunities to practice, the students were enthusiastic and ready to start. I had organized the i-pads and found places for the recordings to happen. Some initial observations in comparison to our first try (pumpkin patch recording) were:

- Having students record in a quiet spot, away from distraction was much more effective. It was private, the students could concentrate, there were no opportunities to “show off” and surprisingly, they didn’t need much adult help. One student, Jack, did a wonderful job of retelling without acting silly like he had previously done. Personally, this method was less stressful for me as a teacher and definitely built my confidence as a user of technology.

- Because this was our second time using Adobe Voice, the students were much more comfortable with the process. They weren’t distracted by the actual device and were able to move on to the actual recording.

- I believe that the students were motivated by the “look” of their final product. The musical background, their own illustrations and the overall appearance of the recording was a good way to end this retelling. Many students asked if they could do it again.

- Finally, we celebrated our successes by sharing our stories with others. The students enjoyed this process and were proud of their hard work.

- Having students record in a quiet spot, away from distraction was much more effective. It was private, the students could concentrate, there were no opportunities to “show off” and surprisingly, they didn’t need much adult help. One student, Jack, did a wonderful job of retelling without acting silly like he had previously done. Personally, this method was less stressful for me as a teacher and definitely built my confidence as a user of technology.

- Nov. 7: Looking at the Evidence

My primary interest was to get a picture of how my scaffolding activities affected the retelling of “The Tailor”. I based my data collections on my observations from the latest Adobe Voice recordings as well as anecdotal notes I had made from student behaviours/pictures I had taken. I chose to look at the scaffolding techniques that I had used and how these had impacted the student’s ability to retell/record the story. I also compiled a snapshot of each student’s recording to get an overall picture of the results of the scaffolds I had used. Here are the results:

Overall snapshot of 16 students (criteria: is able to tell the entire story including the intro. and ending; uses a clear voice; remembers the repetitions/patterns of the story; operates Adobe Voice effectively)

My primary interest was to get a picture of how my scaffolding activities affected the retelling of “The Tailor”. I based my data collections on my observations from the latest Adobe Voice recordings as well as anecdotal notes I had made from student behaviours/pictures I had taken. I chose to look at the scaffolding techniques that I had used and how these had impacted the student’s ability to retell/record the story. I also compiled a snapshot of each student’s recording to get an overall picture of the results of the scaffolds I had used. Here are the results:

Overall snapshot of 16 students (criteria: is able to tell the entire story including the intro. and ending; uses a clear voice; remembers the repetitions/patterns of the story; operates Adobe Voice effectively)

exceeding expectations: 1 student (6%) fully meeting expectations: 7 students (44%) minimally meeting expectations: 5 students (31%) not meeting expectations: 3 students (19%)

1. Scaffold: Making and using a story map

15/16 students successfully made a story map that represented "The Tailor". One students needed support to complete it. 16/16 students used their own story maps as a prompt to retell the story (the story map on the yellow paper strips was used first and then later when it was transferred onto the i-pads).

2. Scaffold: Practicing to say an introduction and ending

16/16 students introduced and ended their story correctly as practiced (this may also have been because they were prompted by the beginning and ending frames on the i-pads).

3. Scaffold: Learning to use Adobe Voice

Student needing coaching: 1 (6%) Student didn't want to record: 1 (6%) Students having some difficulty but no assistance require: 4 (25%) Students experiencing no difficulty: 10 (63%)

4. Scaffold: Incorporating repeated patterns in the retelling

10/14 (71%) students

- Some observations and recommendations

An overall snapshot where 75% of my students are meeting criteria tells me that learning took place and that the scaffolding may have had a positive effect on retelling abilities. It also suggest that my students are ready to move on to something new and perhaps more challenging.

An overall snapshot where 75% of my students are meeting criteria tells me that learning took place and that the scaffolding may have had a positive effect on retelling abilities. It also suggest that my students are ready to move on to something new and perhaps more challenging.It may be useful to make an Anchor Chart that reminds students of what a good storyteller looks like.

There are pros and cons to using only one way to collect evidence. Adobe Voice is an easy App to use and gets good results, but I’m thinking of my one student (Jordan) who made silly noises on his initial pumpkin patch recording and then refused to retell the story of “The Tailor”. Jordan is extremely shy but usually not defiant. Speaking is often difficult for him and he acts silly or shuts down if he begins to feel uncomfortable. There are other ways to encourage him to speak or to offer opportunities for retelling in more.comfortable, non-threatening activities. An example was when I quickly gathered a small group of children around the -pad and we had fun saying “my name is…” and creating a short recording of it. Jordan was in this group. There was no pressure and he joined in whole-heartedly (see the example under the post “The Tailor: Our final product” called “my name is…”).

When listening to the recordings, I noticed that many students had difficulty choosing words when moving from one frame to the next. Another scaffolding activity might be to teach some connecting words that will enable them to move smoothly from one idea to the next

63% of my students had little or no difficulty using Adobe Voice. It may be time to provide more instruction about the App and opportunities to use it in other ways (i.e. recording finding in Science or documenting Math activities). I have also made note of the 4 students who may need some assistance next time we use the App.

A wonder: What would happen if I took away the story map prompts. How well could my students retell? Would I see more creativity and imagination? Would they feel freed up from following the pictures or would they experience more difficulty?

- Flipping the Coin: The relationship between oral language and scaffolding

The purpose of my Field Study is to investigate a variety of scaffolding activities to encourage and develop greater oral language skills in storytelling. My readings around this topic have lead to a wondering: can oral language aid in the scaffolding process? Are these two ideas reciprocally connected? Vygotsky’s social view of learning suggests that they are. He believes that knowledge is collaboratively constructed. There is active participation that enables learners to construct and transform language. How does this collaboration happen? What does this active participation look like? It appears to be had through oral communication; through external dialogue. Mercer (1994) suggests that “through talk, in particular, information and ideas can be shared, points of view explored and explanations presented. These new ways of thinking and understanding may represent only minor shifts, but there are significant in the ongoing construction of knowledge and the development of alternative perspectives.” The ability to communicate ideas with others helps us to talk through our way to understanding. Effective scaffolding allows and assists a movement beyond actual development to a level of potential development (ZPD) (2001, 24). Vygotsky further argues that:

The purpose of my Field Study is to investigate a variety of scaffolding activities to encourage and develop greater oral language skills in storytelling. My readings around this topic have lead to a wondering: can oral language aid in the scaffolding process? Are these two ideas reciprocally connected? Vygotsky’s social view of learning suggests that they are. He believes that knowledge is collaboratively constructed. There is active participation that enables learners to construct and transform language. How does this collaboration happen? What does this active participation look like? It appears to be had through oral communication; through external dialogue. Mercer (1994) suggests that “through talk, in particular, information and ideas can be shared, points of view explored and explanations presented. These new ways of thinking and understanding may represent only minor shifts, but there are significant in the ongoing construction of knowledge and the development of alternative perspectives.” The ability to communicate ideas with others helps us to talk through our way to understanding. Effective scaffolding allows and assists a movement beyond actual development to a level of potential development (ZPD) (2001, 24). Vygotsky further argues that:“external dialogues in which learners take part are gradually internalized to construct the resources for thinking: outer speech eventually becomes inner thinking. As learners talk through a problem, or as they ‘talk their way to understanding’, they are developing the‘thinking’ tools for later problem-solving tools which will eventually becomeinternalized and construct the resources for independent thinking.”

The process of internalizing knowledge; for making sense of our world through dialogue is scaffolded by more and more opportunities to dialogue and make meaning. Being able to effectively communicate through oral language directly affects the scaffolding that occurs. Practically speaking, oral language development does much more than create good storytellers, it is critical in the process of learning.

“It follows, then, that the kinds of talk that occur in the classroom are critical in the development of how students ‘learn to learn’ through language and ultimately how they learn to think.” (2001, 25)

Reading Reference: Hamilton & Gibbons (2001). What is Scaffolding? In Hammond, J. (Ed.), Scaffolding – Teaching and Learning in Language and Literacy Education.

- Nov. 23: Making Connections

Is there a connection between cognitive tools, scaffolding and ZPD (Zone of Proximal Development)? Today, as I was attempting to synthesize my readings with my data I came to the conclusion that there is. This was a big “aha” moment for me. As yet, I hadn’t thought to bring my studies of Imaginative Education into the work I was doing in my field study. As I was thinking about where I would go next with my field study lessons (in storytelling), it occurred to me that it would be possible and perhaps very effect to infuse a storytelling opportunity into my Curriculum Design Project. What better way than to represent the journey of a water molecule through a story. What better way to understand my inquiries so for than to meld them both together into a single lesson!

This excited me.

As I began to think about the practical part of developing the lesson it seemed important to make some connections with my storytelling unit and cognitive tools first. I started writing ideas on some stickies. On each sticky I wrote one scaffolding activity that I had already employed with my students to help them be effective storytellers (when telling the story of “The Tailor”). Then under that activity I wrote corresponding cognitive tools that were used. Here are a few examples:

1. The scaffold of the Virginia Reel activity used the cognitive tools of game and pattern (rotating around and moving to the next position)

2. The scaffold of Telling the Wall used the cognitive tools of rhyme and rhythm (telling the patterns and repetitions in the story); while telling the story the students employed forming images, binary opposites (give/take); drama (using voice inflection and emotion to tell the story)

3. The scaffold of creating a Story Map used the cognitive tools of imagery (visual representation of the story), binary opposites, pattern (in the drawings of the story)

4. The scaffold of Around the Circle used the cognitive tools of game, rhythm, binary opposites

My sticky activity (and data analysis) clearly pointed out that as we had moved through some of these scaffolds and cognitive tools, it was time to push the students forward in their storytelling abilities, their use of Adobe Voice and perhaps the medium of storytelling. Egan suggests that “we need to provide opportunities for students to begin using some of the later tool kit even if in embryonic form. As with young children’s use of embryonic tools of literacy, in Vygotsky’s terms, this might be seen as drawing the students forward in their ‘zone of proximal development.'” (Egan, 2005, pg.82).

The combination or synthesis of scaffolding activities and cognitive tools (can they be the same?) had lead my students to the place of needing more tools in their kit or scaffolds in order to move them into a place of greater learning opportunities. Complexity theorists see this place as the “edge of chaos”. This is where they claim new life/learning happens. “Teaching and learning seem to be more about expanding the space of the possible and creating conditions for the emergence of the as-yet unimagined, rather than perpetuating entrenched habit of interpretation.” (Fels and Belliveau, pg. 26) Vygotsky’s ZPD becomes then, a location where the of scaffolding learning among students happens: scaffolding that includes the use of Egan’s cognitive tools.

With all this in mind, I have set forth to create a series of lessons that will be employed through the use of scaffolding activities and cognitive tools. The idea of oral language development (storytelling) as the umbrella focus and Vygotsky’s ZPD as my aim for providing an “action site of learning” (from Performative Inquiry, Fels and Belliveau).

Is there a connection between cognitive tools, scaffolding and ZPD (Zone of Proximal Development)? Today, as I was attempting to synthesize my readings with my data I came to the conclusion that there is. This was a big “aha” moment for me. As yet, I hadn’t thought to bring my studies of Imaginative Education into the work I was doing in my field study. As I was thinking about where I would go next with my field study lessons (in storytelling), it occurred to me that it would be possible and perhaps very effect to infuse a storytelling opportunity into my Curriculum Design Project. What better way than to represent the journey of a water molecule through a story. What better way to understand my inquiries so for than to meld them both together into a single lesson!

This excited me.

As I began to think about the practical part of developing the lesson it seemed important to make some connections with my storytelling unit and cognitive tools first. I started writing ideas on some stickies. On each sticky I wrote one scaffolding activity that I had already employed with my students to help them be effective storytellers (when telling the story of “The Tailor”). Then under that activity I wrote corresponding cognitive tools that were used. Here are a few examples:

1. The scaffold of the Virginia Reel activity used the cognitive tools of game and pattern (rotating around and moving to the next position)

2. The scaffold of Telling the Wall used the cognitive tools of rhyme and rhythm (telling the patterns and repetitions in the story); while telling the story the students employed forming images, binary opposites (give/take); drama (using voice inflection and emotion to tell the story)

3. The scaffold of creating a Story Map used the cognitive tools of imagery (visual representation of the story), binary opposites, pattern (in the drawings of the story)

4. The scaffold of Around the Circle used the cognitive tools of game, rhythm, binary opposites

My sticky activity (and data analysis) clearly pointed out that as we had moved through some of these scaffolds and cognitive tools, it was time to push the students forward in their storytelling abilities, their use of Adobe Voice and perhaps the medium of storytelling. Egan suggests that “we need to provide opportunities for students to begin using some of the later tool kit even if in embryonic form. As with young children’s use of embryonic tools of literacy, in Vygotsky’s terms, this might be seen as drawing the students forward in their ‘zone of proximal development.'” (Egan, 2005, pg.82).

The combination or synthesis of scaffolding activities and cognitive tools (can they be the same?) had lead my students to the place of needing more tools in their kit or scaffolds in order to move them into a place of greater learning opportunities. Complexity theorists see this place as the “edge of chaos”. This is where they claim new life/learning happens. “Teaching and learning seem to be more about expanding the space of the possible and creating conditions for the emergence of the as-yet unimagined, rather than perpetuating entrenched habit of interpretation.” (Fels and Belliveau, pg. 26) Vygotsky’s ZPD becomes then, a location where the of scaffolding learning among students happens: scaffolding that includes the use of Egan’s cognitive tools.

With all this in mind, I have set forth to create a series of lessons that will be employed through the use of scaffolding activities and cognitive tools. The idea of oral language development (storytelling) as the umbrella focus and Vygotsky’s ZPD as my aim for providing an “action site of learning” (from Performative Inquiry, Fels and Belliveau). - Jan. 15: A Puzzle Metaphor

Our first assignment for EDPR 527 was to think of a metaphor that represented the idea of a learning community. I choose to use a puzzle. I had worked on and completed this puzzle during the Christmas holidays. I was closely connected with the challenge, struggle and triumph of finding pieces that worked together to create a whole. It seemed fitting that what I was experiencing in puzzle building, could also represent some of the characteristics found in a learning community.

Pieces of the puzzle inform the whole. Each piece is original and has the unique one-of-a kind qualities that allows it to fit into only one place. It’s uniqueness is needed to create the big picture. Members of the learning community do just this. Each person brings ideas, challenges, struggles and triumphs to the community. Each person is needed to complete the whole. Without a piece, the puzzle is not finished. Individual talents and abilities are what make a learning community special and often drive the ideas and direction of that community. Conversely, the whole of the puzzle helps to inform the individual pieces. I needed the completed picture of the puzzle to give clues as to where each piece fit. The entire picture helped make sense of the details and uniqueness of the individual pieces. So it is with a learning community. Sharing ideas, critiquing each other, being challenged in thinking are only a few things that the whole community offers to it’s individual members.

It was a great disappointment for me to discover that one of my puzzle pieces was missing. There was a hole in the big picture. I had to think that in learning communities, some members may feel that they don’t have a voice. They may feel insignificant and unimportant. In the end, it is a loss for the whole group. How do we encourage those who are scared or intimidated to join in and make the picture complete?

Our first assignment for EDPR 527 was to think of a metaphor that represented the idea of a learning community. I choose to use a puzzle. I had worked on and completed this puzzle during the Christmas holidays. I was closely connected with the challenge, struggle and triumph of finding pieces that worked together to create a whole. It seemed fitting that what I was experiencing in puzzle building, could also represent some of the characteristics found in a learning community.

Pieces of the puzzle inform the whole. Each piece is original and has the unique one-of-a kind qualities that allows it to fit into only one place. It’s uniqueness is needed to create the big picture. Members of the learning community do just this. Each person brings ideas, challenges, struggles and triumphs to the community. Each person is needed to complete the whole. Without a piece, the puzzle is not finished. Individual talents and abilities are what make a learning community special and often drive the ideas and direction of that community. Conversely, the whole of the puzzle helps to inform the individual pieces. I needed the completed picture of the puzzle to give clues as to where each piece fit. The entire picture helped make sense of the details and uniqueness of the individual pieces. So it is with a learning community. Sharing ideas, critiquing each other, being challenged in thinking are only a few things that the whole community offers to it’s individual members.

It was a great disappointment for me to discover that one of my puzzle pieces was missing. There was a hole in the big picture. I had to think that in learning communities, some members may feel that they don’t have a voice. They may feel insignificant and unimportant. In the end, it is a loss for the whole group. How do we encourage those who are scared or intimidated to join in and make the picture complete? - Feb. 10: A Spacious Place

Today:

maybe I’ll get out of bed…or not…

actually that was yesterday too. My body feels like it is weighted down and difficult to move. I have muscle aches and nausea. Food is a perverse obsession. I try to fold laundry, but only make it through half the load.

I have laughed – about this all. I started a new puzzle. Played through most of the movie theme songs from our Disney mega-book, began reading a new novel, napped, watched netflix, pondered all day about walking outside and then actually ventured out – the stars were spectacular!

It’s time to shave my hair – I wear a hurley scull cap to cover it up. I think my eye lashes are falling out too…

In it all, I am being “wooed from the jaws of distress to a spacious place free from restriction (Job. 36:16). I have been given this picture of a spacious place. I know where it is. On the way up to Stillwood Camp, there is a spacious place.

It is a large, expansive, open field…a place to breath and run unhindered. It is a place of rescue and delight. It’s where I go to find hope and peace…and perhaps…joy. I am thankful for this space. “He brought me out into a spacious place; he rescued me because he delighted in me.” (Ps. 18:19)

Today:

maybe I’ll get out of bed…or not…

actually that was yesterday too. My body feels like it is weighted down and difficult to move. I have muscle aches and nausea. Food is a perverse obsession. I try to fold laundry, but only make it through half the load.

I have laughed – about this all. I started a new puzzle. Played through most of the movie theme songs from our Disney mega-book, began reading a new novel, napped, watched netflix, pondered all day about walking outside and then actually ventured out – the stars were spectacular!

It’s time to shave my hair – I wear a hurley scull cap to cover it up. I think my eye lashes are falling out too…

In it all, I am being “wooed from the jaws of distress to a spacious place free from restriction (Job. 36:16). I have been given this picture of a spacious place. I know where it is. On the way up to Stillwood Camp, there is a spacious place.

It is a large, expansive, open field…a place to breath and run unhindered. It is a place of rescue and delight. It’s where I go to find hope and peace…and perhaps…joy. I am thankful for this space. “He brought me out into a spacious place; he rescued me because he delighted in me.” (Ps. 18:19) - Feb. 15: Reflection on the professional development of two teacher friends

I am fortunate to be blessed with a teacher-friend – Rhona. The basis of our friendship began about 7 years at the start of a job-share position. Having shared a classroom with a number of teachers over my career, it was soon clear to me that this particulate situation was different. From the very start, I felt peace, a shared purpose and commitment to the task – caring for each other and for our students and a baseline understanding about what teaching should look like philosophically.

In reflecting on this article, I am able to draw on some specific examples that resonate clearly with my own experience. Nodding speaks about fidelity: not to a principle or attribute, but “rather guided by an ethic of care for the other” It should be “refined through a deep consideration for a friend as a vulnerable human being.” (p. 26-27). My experience with Rhona has been cultivated and grown by her openness and willingness to accept me as a whole person. What I bring to the table is more than just the curriculum I teach. She has valued and affirmed my role as a mother, wife, daughter – my passions, my concerns, my health – my misgivings and my fears. Sonu reflects that our spaces for friendships need to have greater attention on sustaining feelings of safety and trust. The “character of the relationship takes precedence over the content of the curriculum” (p.30).

Perhaps, though, a guiding feature of our friendship centres around a common philosophical stance about the balance of academic and emotional needs of our students. This basis of understanding has opened up opportunity for safe risk-taking, critique and reflection.

I am fortunate to be blessed with a teacher-friend – Rhona. The basis of our friendship began about 7 years at the start of a job-share position. Having shared a classroom with a number of teachers over my career, it was soon clear to me that this particulate situation was different. From the very start, I felt peace, a shared purpose and commitment to the task – caring for each other and for our students and a baseline understanding about what teaching should look like philosophically.

In reflecting on this article, I am able to draw on some specific examples that resonate clearly with my own experience. Nodding speaks about fidelity: not to a principle or attribute, but “rather guided by an ethic of care for the other” It should be “refined through a deep consideration for a friend as a vulnerable human being.” (p. 26-27). My experience with Rhona has been cultivated and grown by her openness and willingness to accept me as a whole person. What I bring to the table is more than just the curriculum I teach. She has valued and affirmed my role as a mother, wife, daughter – my passions, my concerns, my health – my misgivings and my fears. Sonu reflects that our spaces for friendships need to have greater attention on sustaining feelings of safety and trust. The “character of the relationship takes precedence over the content of the curriculum” (p.30).

Perhaps, though, a guiding feature of our friendship centres around a common philosophical stance about the balance of academic and emotional needs of our students. This basis of understanding has opened up opportunity for safe risk-taking, critique and reflection.  Our friendship that is built on trust and vulnerability has opened a space for me to embrace a different way of understanding. I echo the metaphor of “another self” (Zalloua, 2002, p.28): an opportunity when the “self breaks out of itself to courageously confront inner flaws and inadequacies.” I have seen, by watching, listening and dialoguing with Rhona that my approaches to teaching have lacked confidence and risk. Over the years, I have learned from her: to be more firm and certain with parent advice, to cover my bases in evaluation and assessment and to listen to others and be open to new ideas. She has encouraged yet challenged my beliefs. This has given me the OK to follow my instincts with greater enthusiasm and conviction.

In conclusion, I would like to draw on a more recent example of care. When I was diagnosed with cancer this past fall, Rhona’s care for me embodied my wholeness. She continued to treat me as a professional; seeing my role as a teacher as valid and useful despite my illness.

Our friendship that is built on trust and vulnerability has opened a space for me to embrace a different way of understanding. I echo the metaphor of “another self” (Zalloua, 2002, p.28): an opportunity when the “self breaks out of itself to courageously confront inner flaws and inadequacies.” I have seen, by watching, listening and dialoguing with Rhona that my approaches to teaching have lacked confidence and risk. Over the years, I have learned from her: to be more firm and certain with parent advice, to cover my bases in evaluation and assessment and to listen to others and be open to new ideas. She has encouraged yet challenged my beliefs. This has given me the OK to follow my instincts with greater enthusiasm and conviction.

In conclusion, I would like to draw on a more recent example of care. When I was diagnosed with cancer this past fall, Rhona’s care for me embodied my wholeness. She continued to treat me as a professional; seeing my role as a teacher as valid and useful despite my illness.  She rallied other staff members to support me in extra-curricular responsibilities (recess duty) that helped to alleviate any unnecessary teaching stress. Rhona stood in the gap for me by practically bringing meals to my home. It takes a selfless kind of person to place care as a vital centre piece in a friendship. This relationship is truly a gift – one that cannot be manufactured, but comes from a heart of giving and looking beyond. I am thankful to be the recipient of that kind of relationship.

Reflection on:

Friendship, Education and Justice Teaching: The Professional Development of Two Teacher-Friends

Debbie Sonu

Hunter College, City University of New York

New York, NY

She rallied other staff members to support me in extra-curricular responsibilities (recess duty) that helped to alleviate any unnecessary teaching stress. Rhona stood in the gap for me by practically bringing meals to my home. It takes a selfless kind of person to place care as a vital centre piece in a friendship. This relationship is truly a gift – one that cannot be manufactured, but comes from a heart of giving and looking beyond. I am thankful to be the recipient of that kind of relationship.

Reflection on:

Friendship, Education and Justice Teaching: The Professional Development of Two Teacher-Friends

Debbie Sonu

Hunter College, City University of New York

New York, NY - Feb. 18: Collaboration and Fresh Grade

Laura Servage in her article “Making Spaces” encourages educators to think about the role of critical reflection energized by dialogue and conversation. Discourse should be authentic and focus on the meanings or “whys” behind why we do things. These times of collaboration should tackle foundational questions and should always be a place for openness to discussion.

Yesterday I had the opportunity to visit with my teacher-friend and colleague, Rhona Pederson. Our relationship is one of openness, “where care is the vital centrepiece” (Sonu, “The Professional Development of Two Teacher-Friends”, p.31). We share a passion for loving children and a desire to create as Nel Noddings encourages, “spaces of invitation that allow us to move beyond the mask and share our vulnerability and humanity”.

Our conversation lead us to the challenge of personalizing our teaching by providing honesty and clarity in our assessment practices. With the introduction of the redesigned BC curriculum in September, we felt that our ideas about how assessment took place should be revisited as well. Rhona and I brainstormed together for things we were already doing that we felt were moving us forward in our vision of what assessment should look like: documenting student work using pictures and audio/visual, sending home work that had clear criteria based on learning outcomes, writing daily messages in student Planners, sharing pictures informally with parents, using iPad (Adobe Voice) recordings at parent/teacher interviews and making use of district technology support.

During my last field study I had begun to use the assessment/reporting tool called Fresh Grade. I was impressed with their vision of “making learning visible with a collaborative learning platform”. This reporting system allows for a better representation of individual learning. Teachers, students and parents have access to this interactive and real-time sharing tool that provides a “window into the classroom”. Fresh Grade seems to align itself with our current educational themes: one of which is personalized learning and assessment.

What to do next? Rhona and I will be collaborating and supporting each other as we hope to begin to use Fresh Grade in September, 2016. I the meantime, I have connected Rhona with the district tech support and they will be providing her with technology to experiment with and try out Fresh Grade for the remainder of the year. I am following Fresh Grade on twitter and continuing to read supporting literature and documents. I will use the Fresh Grade account that I have already set up to learn more and practice using the program.

Laura Servage in her article “Making Spaces” encourages educators to think about the role of critical reflection energized by dialogue and conversation. Discourse should be authentic and focus on the meanings or “whys” behind why we do things. These times of collaboration should tackle foundational questions and should always be a place for openness to discussion.

Yesterday I had the opportunity to visit with my teacher-friend and colleague, Rhona Pederson. Our relationship is one of openness, “where care is the vital centrepiece” (Sonu, “The Professional Development of Two Teacher-Friends”, p.31). We share a passion for loving children and a desire to create as Nel Noddings encourages, “spaces of invitation that allow us to move beyond the mask and share our vulnerability and humanity”.

Our conversation lead us to the challenge of personalizing our teaching by providing honesty and clarity in our assessment practices. With the introduction of the redesigned BC curriculum in September, we felt that our ideas about how assessment took place should be revisited as well. Rhona and I brainstormed together for things we were already doing that we felt were moving us forward in our vision of what assessment should look like: documenting student work using pictures and audio/visual, sending home work that had clear criteria based on learning outcomes, writing daily messages in student Planners, sharing pictures informally with parents, using iPad (Adobe Voice) recordings at parent/teacher interviews and making use of district technology support.

During my last field study I had begun to use the assessment/reporting tool called Fresh Grade. I was impressed with their vision of “making learning visible with a collaborative learning platform”. This reporting system allows for a better representation of individual learning. Teachers, students and parents have access to this interactive and real-time sharing tool that provides a “window into the classroom”. Fresh Grade seems to align itself with our current educational themes: one of which is personalized learning and assessment.

What to do next? Rhona and I will be collaborating and supporting each other as we hope to begin to use Fresh Grade in September, 2016. I the meantime, I have connected Rhona with the district tech support and they will be providing her with technology to experiment with and try out Fresh Grade for the remainder of the year. I am following Fresh Grade on twitter and continuing to read supporting literature and documents. I will use the Fresh Grade account that I have already set up to learn more and practice using the program. - Feb. 23: A Mirror as a Metaphor For a Learning Community

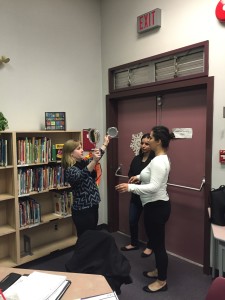

How can a mirror be a metaphor for a learning community?

If you look straight into it, what do you see? You see yourself. Your only focus is the details of your face. Your self image is constructed. You will notice that the mirror also reverses your image, so your perspective of self is somewhat skewed.

Next, walk around with the mirror facing the ceiling. What do you see? Your perspective changes. How you walk around the room is determined by a new reality. Even though your image may be visible, your world has opened up. You are better informed of your space and your actions are determined by its parameters. You may discover things about your environment that are new and interesting – or challenging. Reposition yourself and use the mirror to focus on others around you. Keep your image in the mirror. See how your face becomes part of a larger focus. Now move anywhere to enlarge your picture. Try to include the entire room and its people in your view. Your own image may become a barrier to seeing the larger picture. You choose not to include it in your line of vision. Its all about the big picture. Finally, combine your mirror with someone else. How does the image change? Does your view become infinite?

How can a mirror be a metaphor for a learning community?

If you look straight into it, what do you see? You see yourself. Your only focus is the details of your face. Your self image is constructed. You will notice that the mirror also reverses your image, so your perspective of self is somewhat skewed.

Next, walk around with the mirror facing the ceiling. What do you see? Your perspective changes. How you walk around the room is determined by a new reality. Even though your image may be visible, your world has opened up. You are better informed of your space and your actions are determined by its parameters. You may discover things about your environment that are new and interesting – or challenging. Reposition yourself and use the mirror to focus on others around you. Keep your image in the mirror. See how your face becomes part of a larger focus. Now move anywhere to enlarge your picture. Try to include the entire room and its people in your view. Your own image may become a barrier to seeing the larger picture. You choose not to include it in your line of vision. Its all about the big picture. Finally, combine your mirror with someone else. How does the image change? Does your view become infinite?

The mirror metaphor provides us with an understanding that learning communities are complex. A wonderful binary opposition of self/other presents itself (the individual member/community as a whole). We see a struggle between the contribution of self and the loss of it within the context of a community. Along the continuum there are many offerings of understanding that depend on how the self or the other is perceived, accepted or even forgotten. Is there a place somewhere in between where both the self and the other work together to create equity and wholeness for both? Laura Servage concludes her article “Making Space for Critical Reflection in Professional Learning Communities” with a statement that highlights both the importance of individual reflection and corporate validation in the context of community. We need to make space somewhere along the mirror continuum for both:

The mirror metaphor provides us with an understanding that learning communities are complex. A wonderful binary opposition of self/other presents itself (the individual member/community as a whole). We see a struggle between the contribution of self and the loss of it within the context of a community. Along the continuum there are many offerings of understanding that depend on how the self or the other is perceived, accepted or even forgotten. Is there a place somewhere in between where both the self and the other work together to create equity and wholeness for both? Laura Servage concludes her article “Making Space for Critical Reflection in Professional Learning Communities” with a statement that highlights both the importance of individual reflection and corporate validation in the context of community. We need to make space somewhere along the mirror continuum for both:

“In our present era of accountability, there is a real and justifiable temptation to use collaboration to focus strictly upon instrumental goals that have an immediate impact on classroom practices. However, without some time and reflection devoted to why we do what we do, a sustainable culture of collaboration is unlikely to emerge. In our experiences with our students, it was dialogue about the tough questions – the perennial problems of education – that sent so many of our own students roaring back into their schools, imagining the possible, and ready to innovate with their students and colleagues. Sustaining change momentum, it seems, has much to do with keeping both hope and urgency alive in our work. To do so may require only the simple opportunity to connect, through open-ended reflective dialogue, with our own diverse but generally well-intentioned beliefs and understandings about what it means to educate students.”

“In our present era of accountability, there is a real and justifiable temptation to use collaboration to focus strictly upon instrumental goals that have an immediate impact on classroom practices. However, without some time and reflection devoted to why we do what we do, a sustainable culture of collaboration is unlikely to emerge. In our experiences with our students, it was dialogue about the tough questions – the perennial problems of education – that sent so many of our own students roaring back into their schools, imagining the possible, and ready to innovate with their students and colleagues. Sustaining change momentum, it seems, has much to do with keeping both hope and urgency alive in our work. To do so may require only the simple opportunity to connect, through open-ended reflective dialogue, with our own diverse but generally well-intentioned beliefs and understandings about what it means to educate students.” - Feb. 25: A Mediated Space

In Samaras’ article about teacher research and data collecting, Stefinee Pinnegar (p.178) gives advice as a self-study scholar. She highlights the importance of finding the space between the self and the other when collecting data. This space happens in the midst of practice – between the thoughts and actions of the teacher and the experiences of the student. It is in the tension of this space that we grow and “construct…trustworthy accounts of our practice.”

This idea of “a space between” resonates with the metaphor of the mirror that we used in class to help understand learning communities. The mirror allows many views of self. Some are singular and other views are within the context of the room and people within it. The binary opposites of “self” and “other” lie on either ends of this viewing continuum. Our metaphor attempts to point out that fixating on one opposition or the other does little to create a healthy, collaborative community. Somewhere along this continuum, “practice grows in the space between self and other”. (Stefinee Pinnegar)

Kieran Egan, in his book “Teaching as Storytelling” introduces the idea of “seeking a mediation between our binary organizers”(p.52). He uses an example of a community experiencing a conflict between survival and destruction. Here Egan explains that “the community lives in the balance of survival/destruction”. There is a “dynamic conflict” that is necessary for life. It lies somewhere between these binary oppositions.

Similarly, I would suggest that our learning communities are not examples of binary opposites. There should be a healthy tension between the two that is continuously nurtured and valued. As members of the community, we should be open to allowing our understandings to grow beyond what we see in our own reflections. Our perception of self – our ideas and opinions – should be valued and considered in light of the community as a whole. Living well in this mediated spaced involves listening to others and being open to change and renewal. Or as Laura Selvage points out, it may require “connecting through open-ended reflective dialogue with our own diverse but generally well-intentioned beliefs and understanding about what it means to educate students.” (“Making Space for Critical Reflection in Professional Learning Communities”)

In Samaras’ article about teacher research and data collecting, Stefinee Pinnegar (p.178) gives advice as a self-study scholar. She highlights the importance of finding the space between the self and the other when collecting data. This space happens in the midst of practice – between the thoughts and actions of the teacher and the experiences of the student. It is in the tension of this space that we grow and “construct…trustworthy accounts of our practice.”

This idea of “a space between” resonates with the metaphor of the mirror that we used in class to help understand learning communities. The mirror allows many views of self. Some are singular and other views are within the context of the room and people within it. The binary opposites of “self” and “other” lie on either ends of this viewing continuum. Our metaphor attempts to point out that fixating on one opposition or the other does little to create a healthy, collaborative community. Somewhere along this continuum, “practice grows in the space between self and other”. (Stefinee Pinnegar)

Kieran Egan, in his book “Teaching as Storytelling” introduces the idea of “seeking a mediation between our binary organizers”(p.52). He uses an example of a community experiencing a conflict between survival and destruction. Here Egan explains that “the community lives in the balance of survival/destruction”. There is a “dynamic conflict” that is necessary for life. It lies somewhere between these binary oppositions.

Similarly, I would suggest that our learning communities are not examples of binary opposites. There should be a healthy tension between the two that is continuously nurtured and valued. As members of the community, we should be open to allowing our understandings to grow beyond what we see in our own reflections. Our perception of self – our ideas and opinions – should be valued and considered in light of the community as a whole. Living well in this mediated spaced involves listening to others and being open to change and renewal. Or as Laura Selvage points out, it may require “connecting through open-ended reflective dialogue with our own diverse but generally well-intentioned beliefs and understanding about what it means to educate students.” (“Making Space for Critical Reflection in Professional Learning Communities”) - March 7: A Seed Community (reflection from “Walk Out Walk On”)

A seed contains three parts: embryo, stored food and seed coat. From these three things, a seed has everything it needs to grow a new young plant. Another metaphor for a community? Perhaps. According to the authors of “Walk Out Walk On”, communities who work authentically together “rely on the fact that peoples’ capacity to self-organize is the most powerful change process there is.” Like a seed, they find strength and nourishment from within and change occurs when the resources from all of the community are used. In fact, the resources from all of the community are seen as necessary and required.

A seed contains three parts: embryo, stored food and seed coat. From these three things, a seed has everything it needs to grow a new young plant. Another metaphor for a community? Perhaps. According to the authors of “Walk Out Walk On”, communities who work authentically together “rely on the fact that peoples’ capacity to self-organize is the most powerful change process there is.” Like a seed, they find strength and nourishment from within and change occurs when the resources from all of the community are used. In fact, the resources from all of the community are seen as necessary and required.

Margaret Wheatley and Deborah Frieze have met with several such communities. They call them “Walk Outs”. In each case they have identified some connecting principles for how systemic change is fostered and healthy and resilient communities are created. The image of a seed is strong. A seed carries inside its protective shell life and potential. If communities are to be viewed in the same manner, I wonder where we have so often gone wrong in our attempts to create meaningful spaces of vitality and growth. The authors remind us that many of us cling to the belief that our rescue or answer will come from the outside. How often has that been the case in my own experience, when faced with educational or personal dilemmas, that I have habitually looked to the experts first for advice instead of resourcing my own immediate community. The reasons for this may be numerous, but I would guess that it may have something to do with the kind of community I was seeking.In the Zapatistas community, members believe that they must listen as they walk and talk “at the pace of the slowest.” The journey is honoured and viewed as useful for understanding and teaching. Listening is valued. All members, not just the designated leaders have a voice. In other “Walk Out’ communities, “they let go of complaints, arguments and dramas; they place the work at the centre, invite everyone inside and find solutions to problems that others think unsolvable.” Speed, growth and winning are not evidence of success. Higher scores, more members, expert speakers are not evidence of success. A focus on relationships, diversity and a multitude of perspectives all coming together in one seed pod in a spirit of welcome sheds some light on why these communities thrive and become instruments of change and renewal.

Resource:

“The Role Walk Outs Play in Creating Change”

Margaret Wheatley and Deborah Frieze - March 14: Assessment – BC’s New Curriculum and FreshGrade

I came across some great questions regarding assessment that I can use as a focus/guide for thinking about FreshGrade and BC’s New Curriculum.